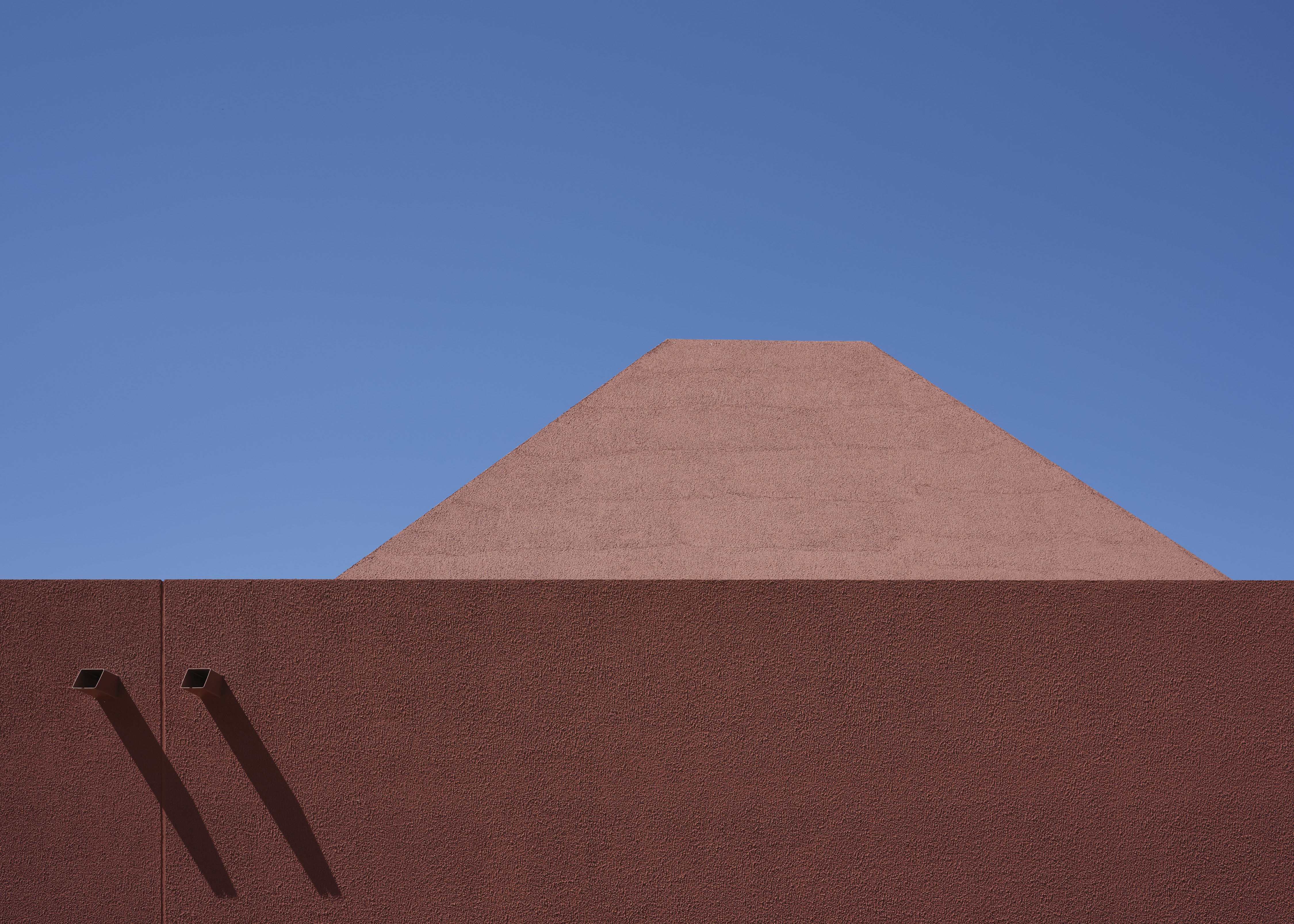

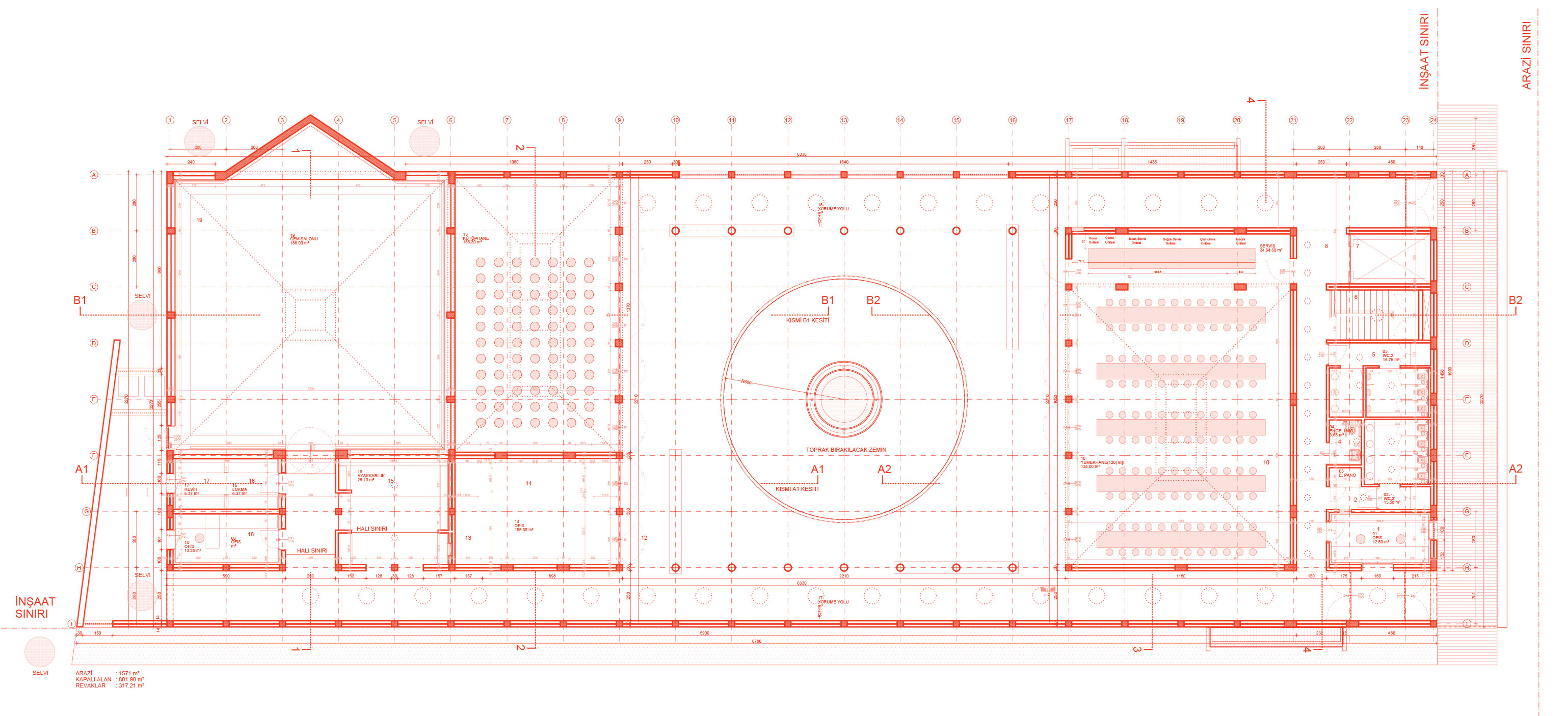

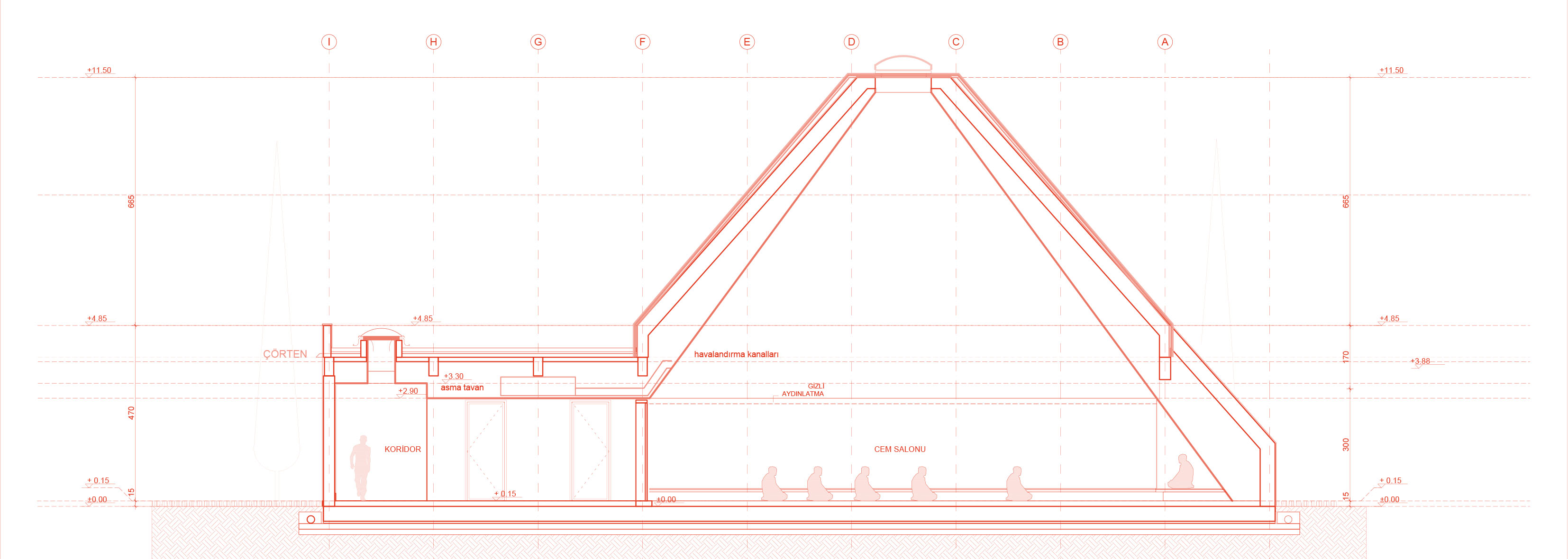

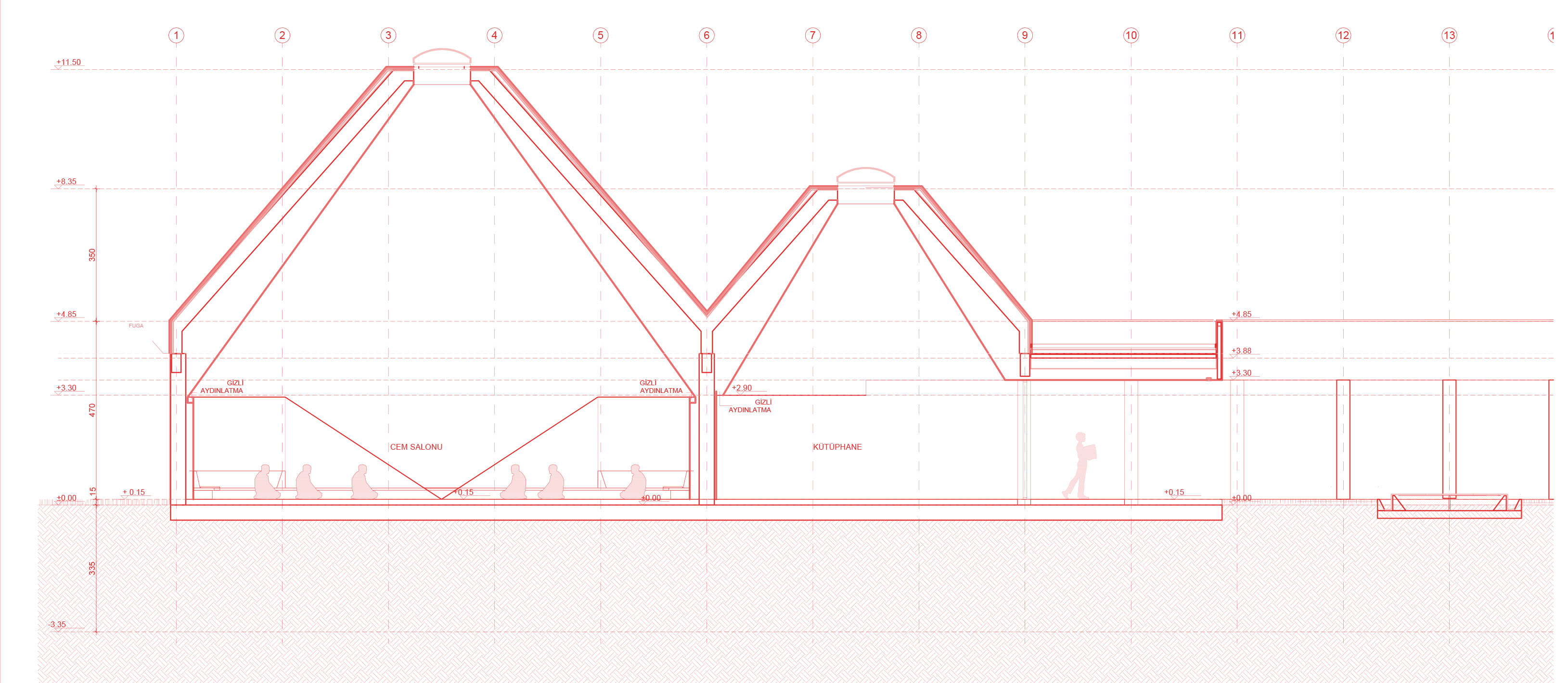

BALÇOVA CEMEVİ

İzmir︎ 2021 ︎ Construction Area: 1118 m2 ︎ Site: 1571 m2 ︎ Religious ︎ Metehan Kahya, Nevzat Sayın, Sami Metin Uludoğan, Serheng Dellal

The cemevis, which were the places of worship of the Alevis who tried to live in secret in the geography of Turkey, did not bear any sign of being a cemevi as a mass effect. But even if the mass was illegible, the interior setup had distinctive features. The overlapped pyramidal roof cover, called “Tütekli Ceiling”*, was considered the characteristic cover system of cemevis, even if it was in other types of buildings, and was covered with a two or four-slope roof like other structures, in a way that would not be visible from the outside. How should these traditional places of worship, which are traditionally maintained in the village and closed to non-Alevis, should be built in the cities in a legible way, under new conditions, for the Alevis who came to the cities with the migration from the countryside to the cities in the 1950s? The Büyük Ocak Djemevi building in the Onar Village of Malatya from the 13th century became our muse; We started with the question of what would be the exterior of a structure with this interior, if it could be, that would express this interior legibly. The four-curved truncated pyramid, which clearly carries the pyramidal form of the tucked ceiling, transformed the mass into the form we seek, as it points both to the concept of "four doors", which is important for Alevis, and the connection between the sky and the light that enters the "square", whose walls we cannot open windows due to its closedness.The library and the soup kitchen were also covered with truncated pyramids, with the sky above them, although with different sizes and shapes from their plans. The inner courtyard, which connects all these units, is completely closed to the road and can be opened towards the park when desired, was shaped based on the circular form of the Alevi semah made by turning. Kızılbaş, which is one of the general descriptive adjectives of Alevis and is sometimes used as a negative charge by non-Alevis, was the reason why we built a red structure out of spite. Our concern was not to produce a tradition, but to do something new by clinging to it, and now, although the structure we have obtained with all these simple and plain reasoning is based on traditional themes, it seems to be a timeless structure as well as being a structure of the present.

DUBAI MOSQUE

Dubai︎ 2019 ︎ Construction Area: 18.500 m2 ︎ Site: 6.000 m2 ︎ Religious ︎ Enis Öncüoğlu, Jülide Arzu Uluçay, Kseniya Mogylevska, Nevzat Sayın, Işıl Düşmez Kocaoğlu, Özge Selen Duran, Serkan Çakıt [with Öncüoğlu Mimarlık]

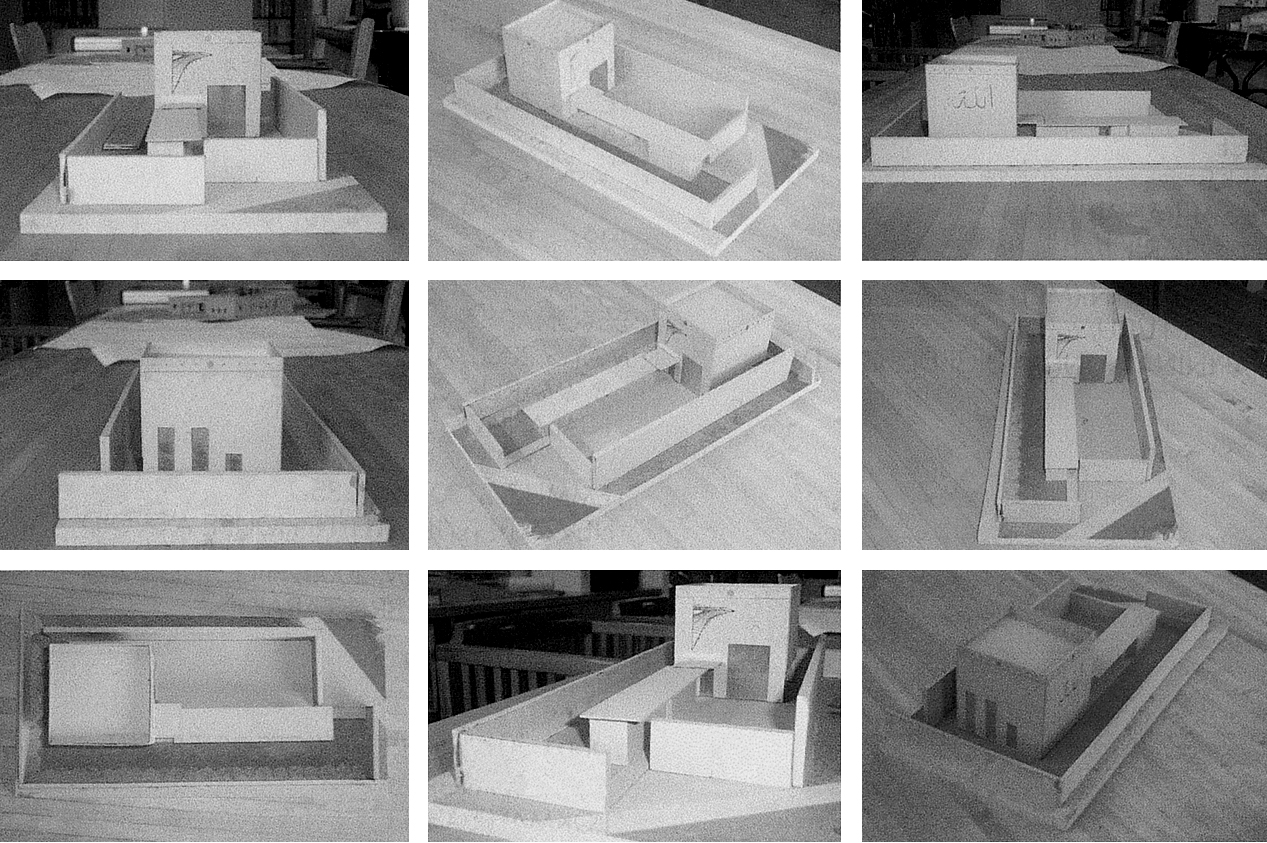

FETHİYE CEMEVİ/MOSQUE

Fethiye/Muğla︎ 2013 ︎ Construction Area: 1.330 m2 ︎ Site: 1.140 m2 ︎ Religious ︎ Hakan Tung, Nevzat Sayın, Sami Metin Uludoğan

The idea of a project that would accommodate both a Cemevi and Mosque was a hot item on the agenda at the time. We had been made part of the project upon the invitation of Fethiye Municipality and the involved parties could not reach an agreement. Some of the notables in the Alevi community agreed with the idea, whereas other considered it to be part of an assimilation project and thus opposed it. We agreed that it was both inevitable and correct to invite representatives of both the Sunni and Alevi communities in Fethiye to a meeting to reach a decision on this generally difficult, even impossible subject. Hence, we began working on the coexistence of a mosque and a cemevi. We held meetings at each phase, explained the developments, and made progress with the criticisms in mind. Just as we were about to begin the implementation of the approved projects, we were asked to continue the work on a different property. We developed a new alternative with the same data, but the project was infinitely postponed and was taken off the table. We never built the structure, but had a wonderful opportunity to develop our ideas about the subject.

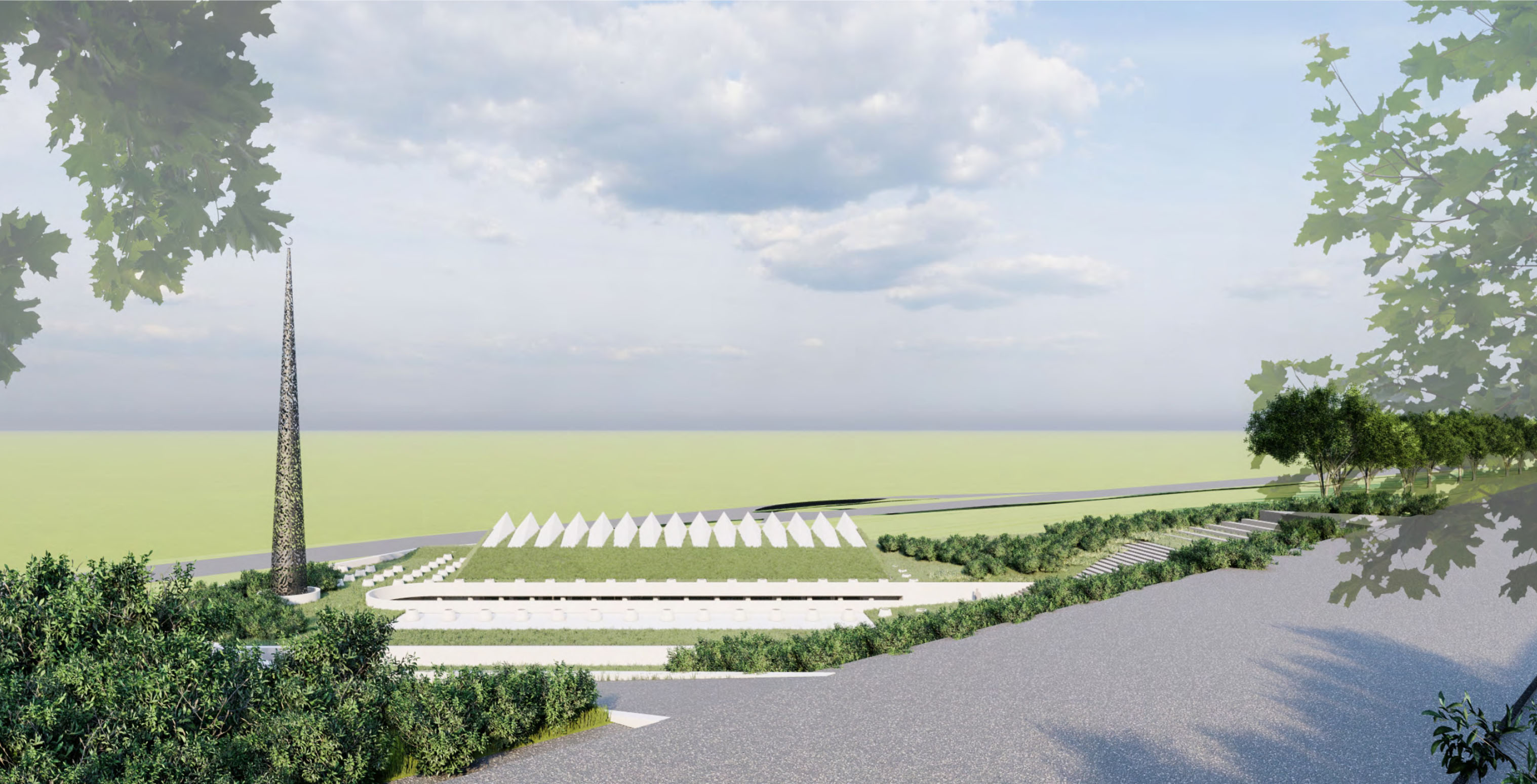

İYTE MOSQUE

İzmir︎ 2020︎ Construction Area: 1255 m2 ︎ Site: 2085 m2 ︎ Religious ︎ Nevzat Sayın, Sami Metin Uludoğan

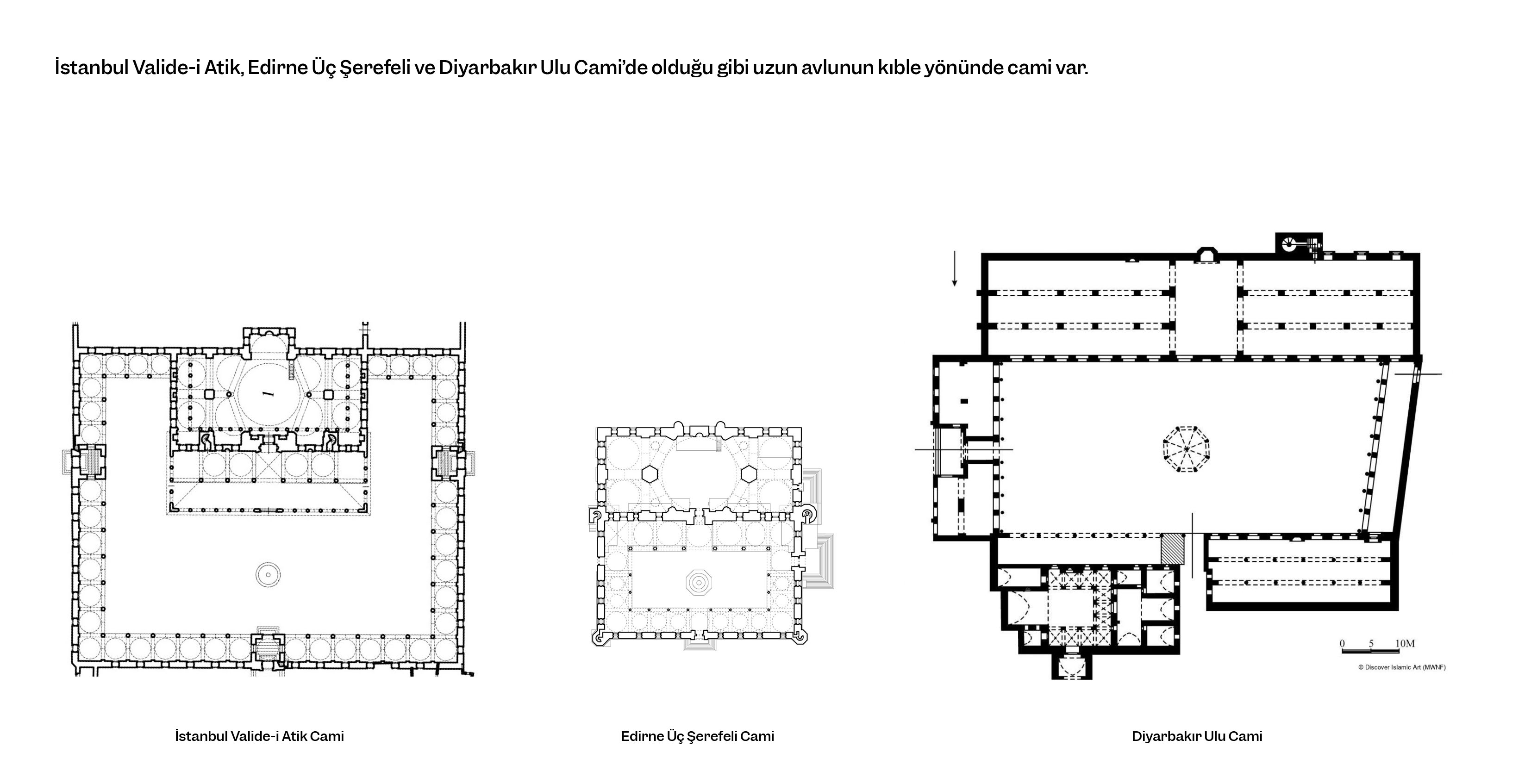

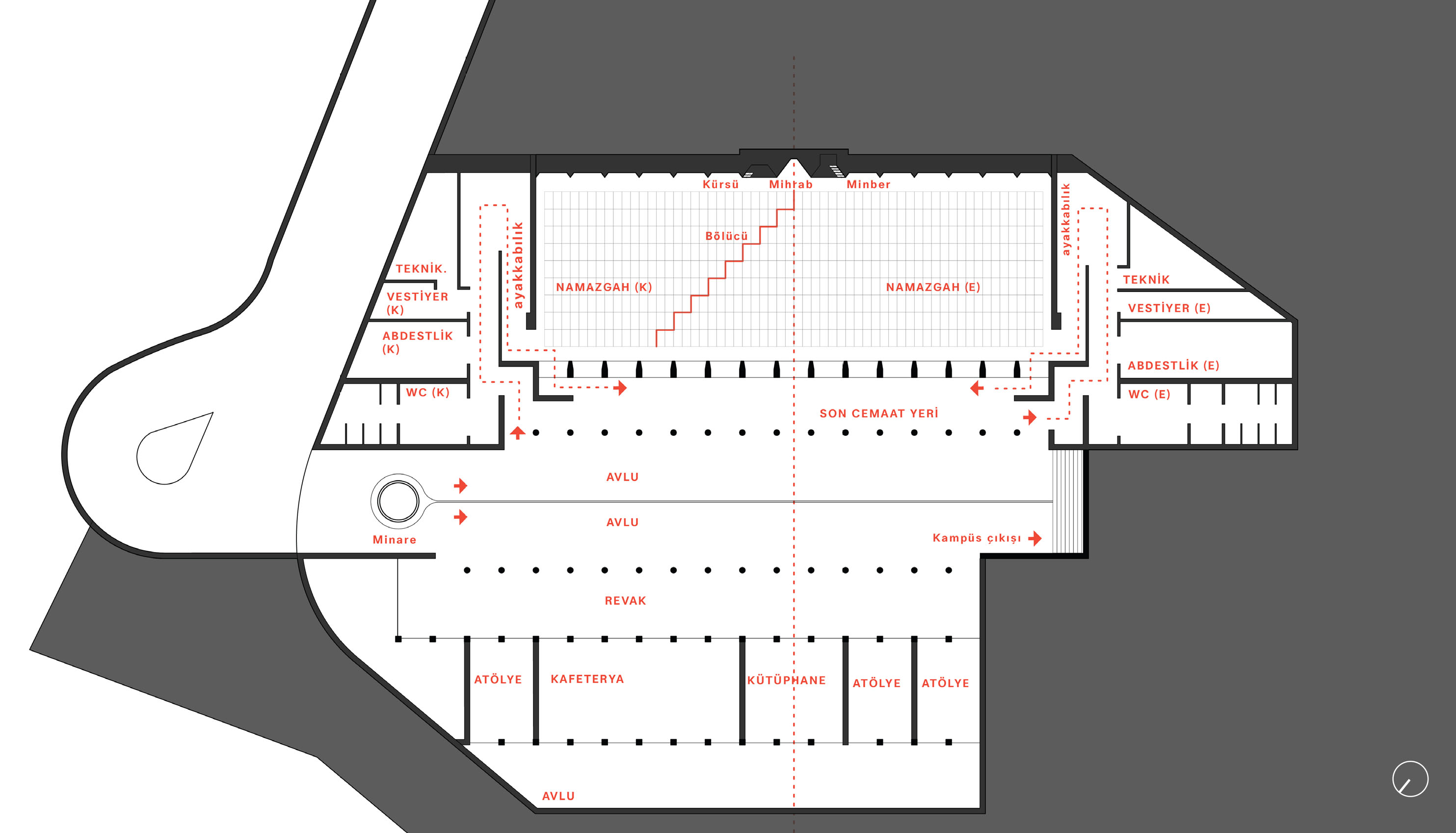

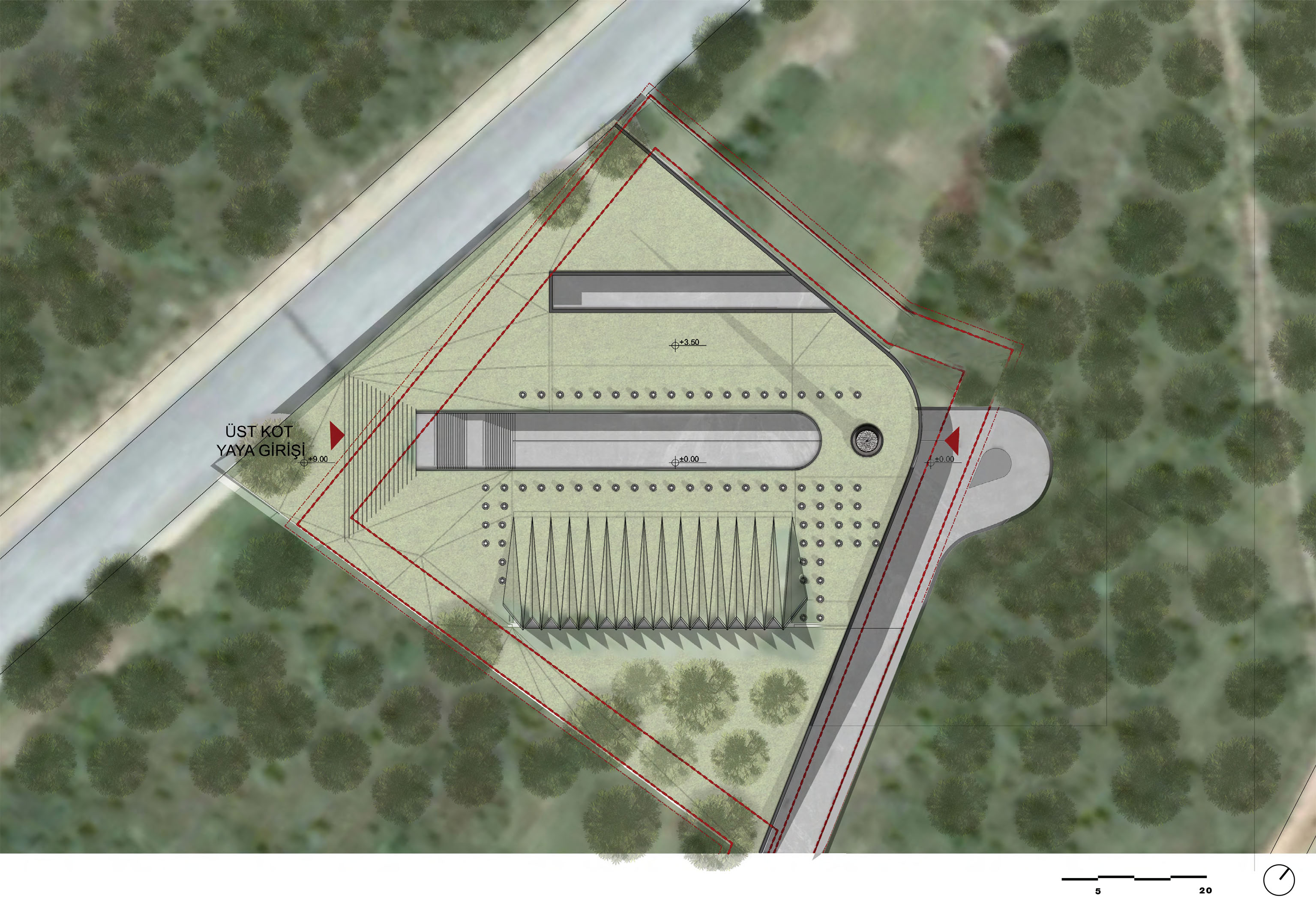

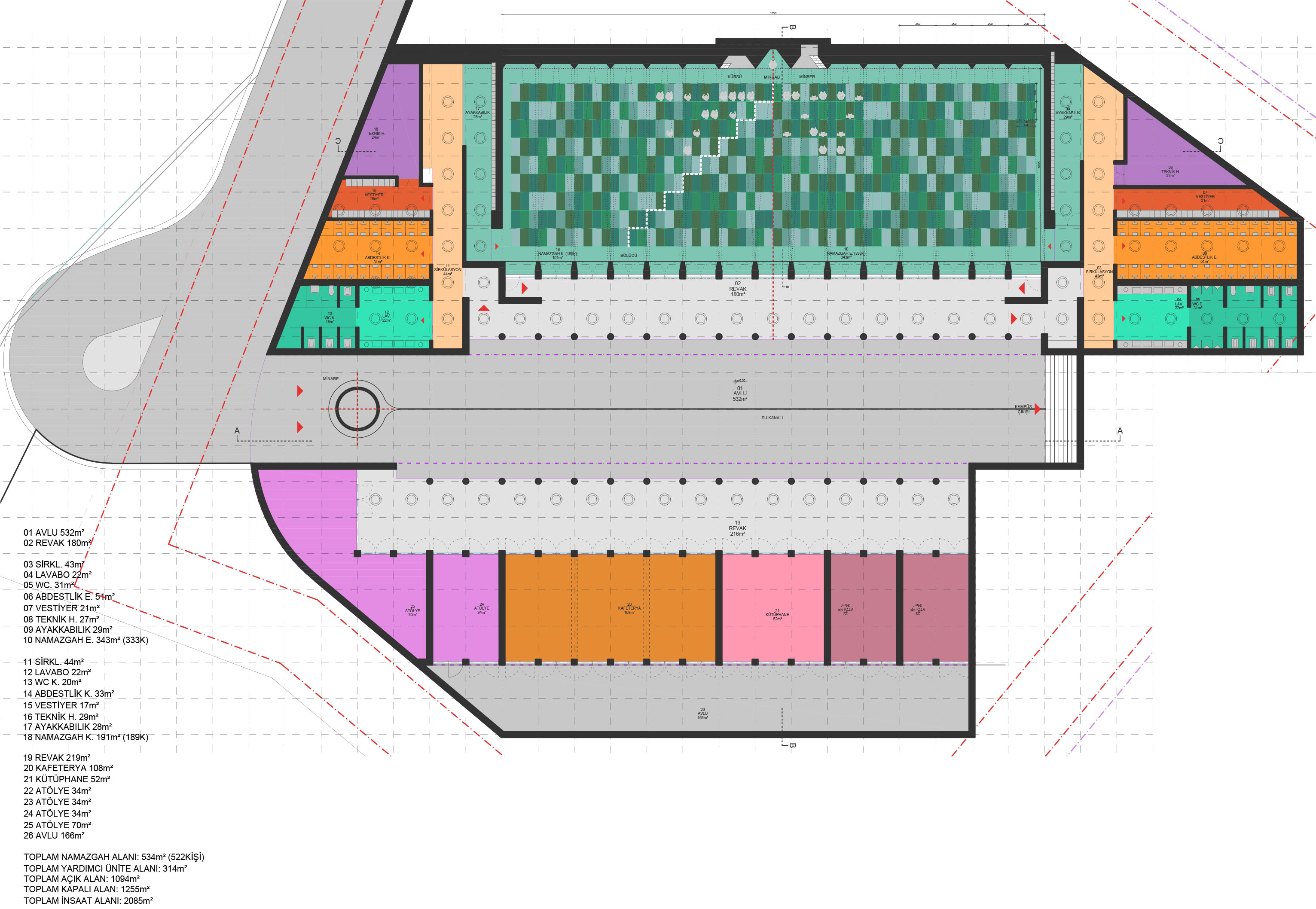

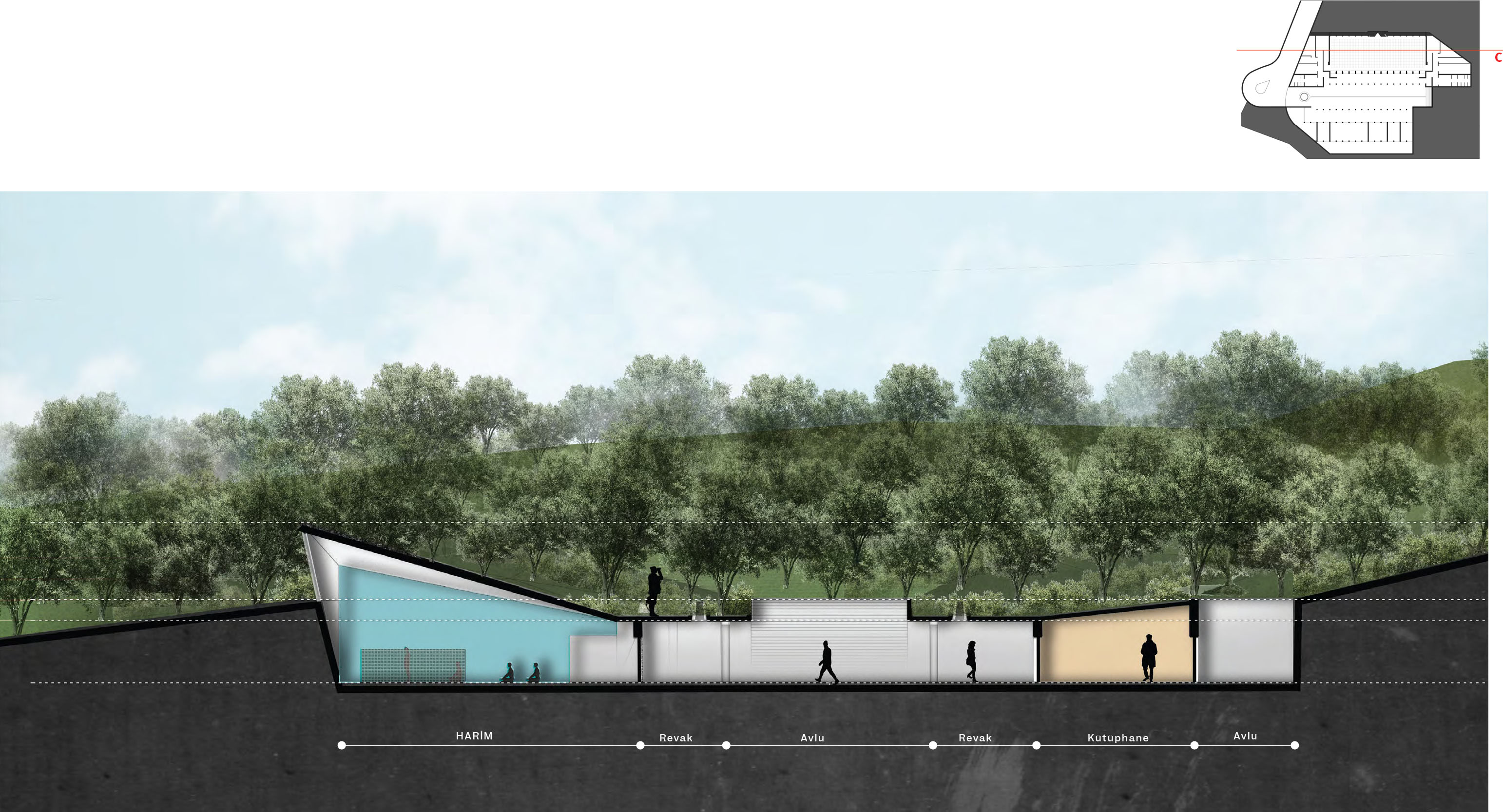

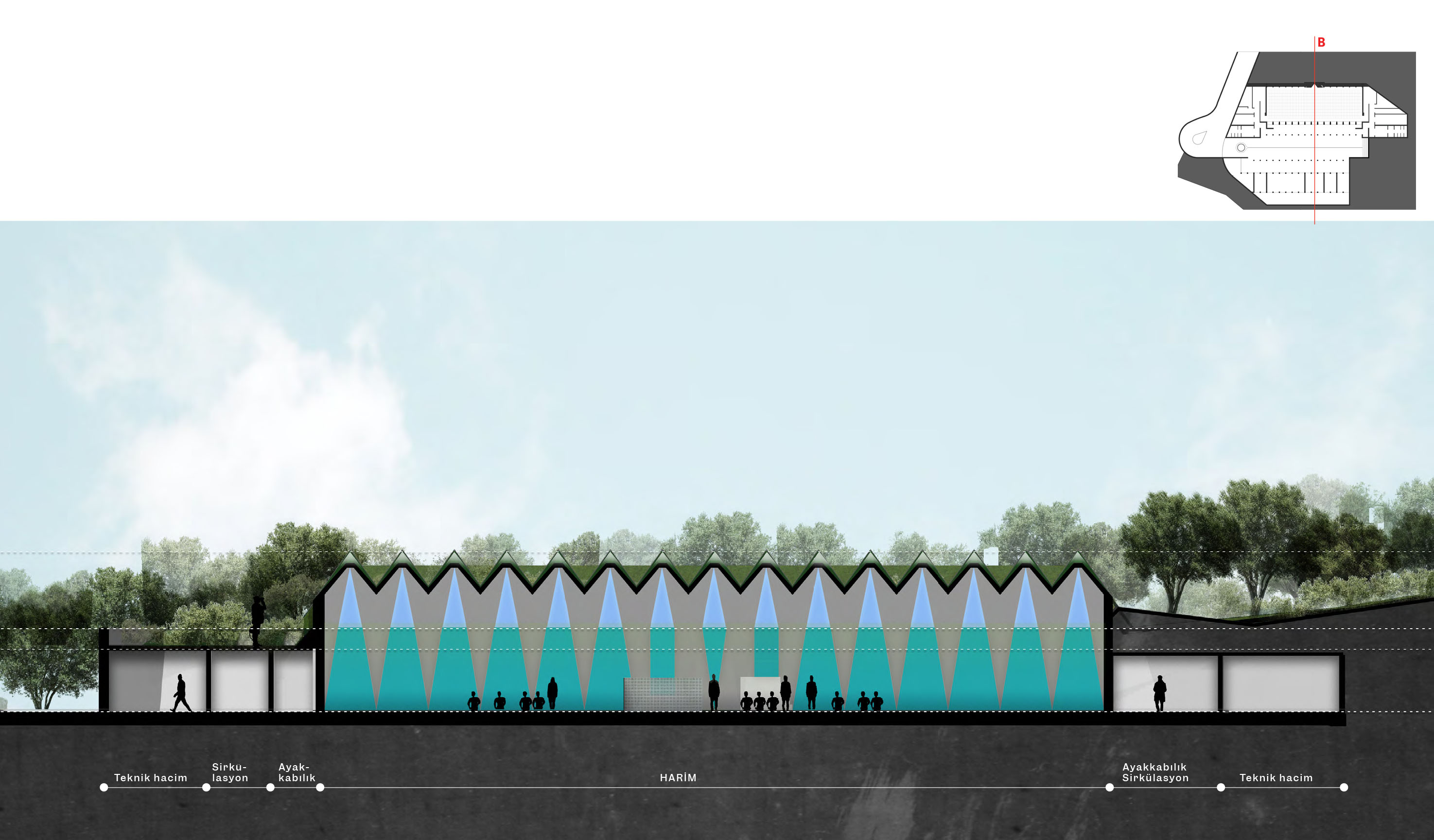

The site, located right next to the main entrance on a sloping terrain, functions as a connection point between the lower and upper roads. Its proximity to the upper road suggests that arrivals from within the campus will approach from the upper side, while arrivals from outside the campus will come from the lower side. The complex, which includes the mosque and its associated units, is situated on either side of a courtyard that serves as the meeting point for these two approaches.The other two sides of the courtyard are defined by the stairs leading down from the upper side and the passageway containing the minaret. This passageway, situated directly opposite the stairs, opens towards the sea, creating a visually and functionally significant axis within the complex. This design ensures that the courtyard acts as a central hub, seamlessly connecting different parts of the site and accommodating the flow of people from both within and outside the campus.

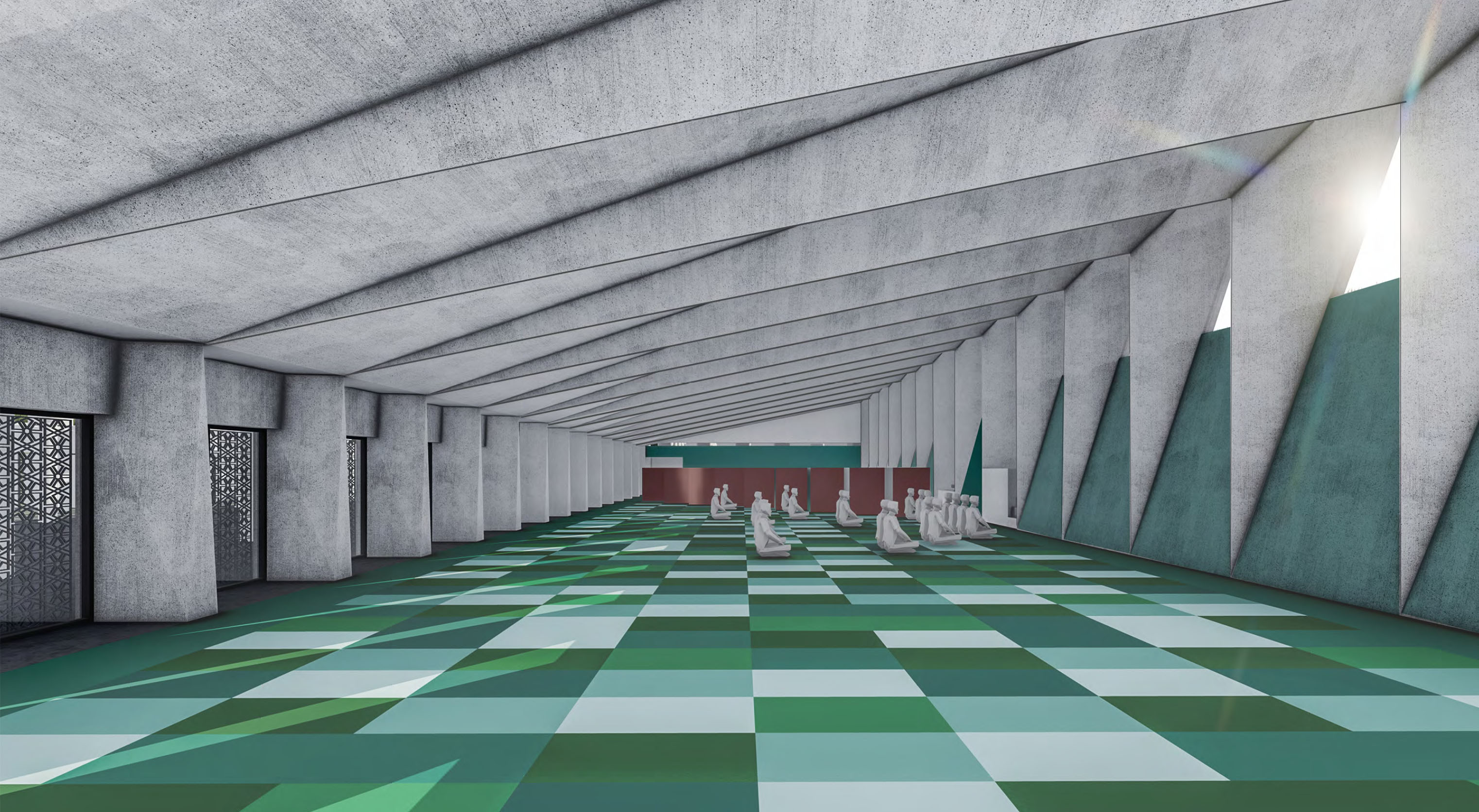

The prayer hall is separated from the last congregation area by windows behind ornamented screens. The courtyard leads to the last congregation area… To maintain the unity of this space, which will be used for prayer most of the time in the Izmir climate, separate entrances for women and men will be provided at the two ends of the last congregation area. This arrangement ensures that the ablution area, lockers for leaving bags, and support units are completely separated. We believe that the connection between the ablution area and the prayer hall has been very well resolved.

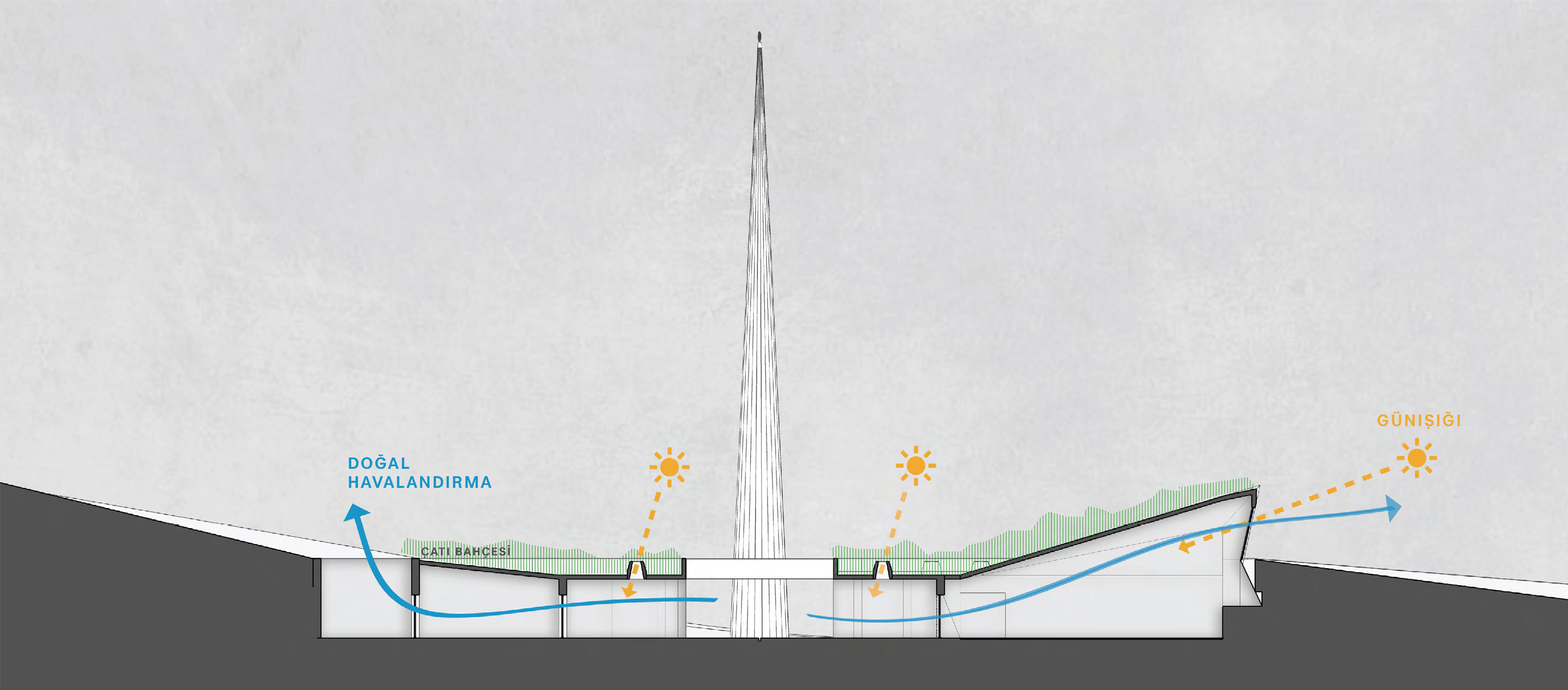

The design concept of an extended front row, supported by the layout within the site, makes the roof rising from the last congregation area towards the qibla wall meaningful. The light entering through the windows on the qibla wall transforms the curved wall into a wall of light. This design not only enhances the spiritual atmosphere of the prayer hall but also emphasizes the architectural harmony between the different elements of the complex.

The roof, composed of folded plates used to span a 15-meter width, aligns with the grand mosque plan and demonstrates that a space for faith can be constructed using high technology, befitting an institution with "high technology" in its name. Additionally, utilizing the large gaps in the folded plates to create a roof garden provides a natural solution for thermal insulation in the Izmir climate. This approach is particularly valuable as it allows for completely natural ventilation, which became crucial when mechanical solutions like air conditioning could not be used during the pandemic. We appreciate this structure for enabling a simple airflow solution: air enters through the windows separating the last congregation area and the prayer hall, rises towards the mihrab wall, and exits through the windows on that wall.

The section on the opposite side of the courtyard, which houses the supporting units of the complex, is similar to the mosque and follows the traditional design of sections entered from a semi-open area under arcades and opening into a rear courtyard. The number and size of these sections can be adjusted based on need. As in the mosque, the roof rising in one direction can carry solar panels. In order not to make the roof height compete with the mosque, we provide the natural ventilation of these spaces with the back courtyard. The courtyard will also enable working in the open space.

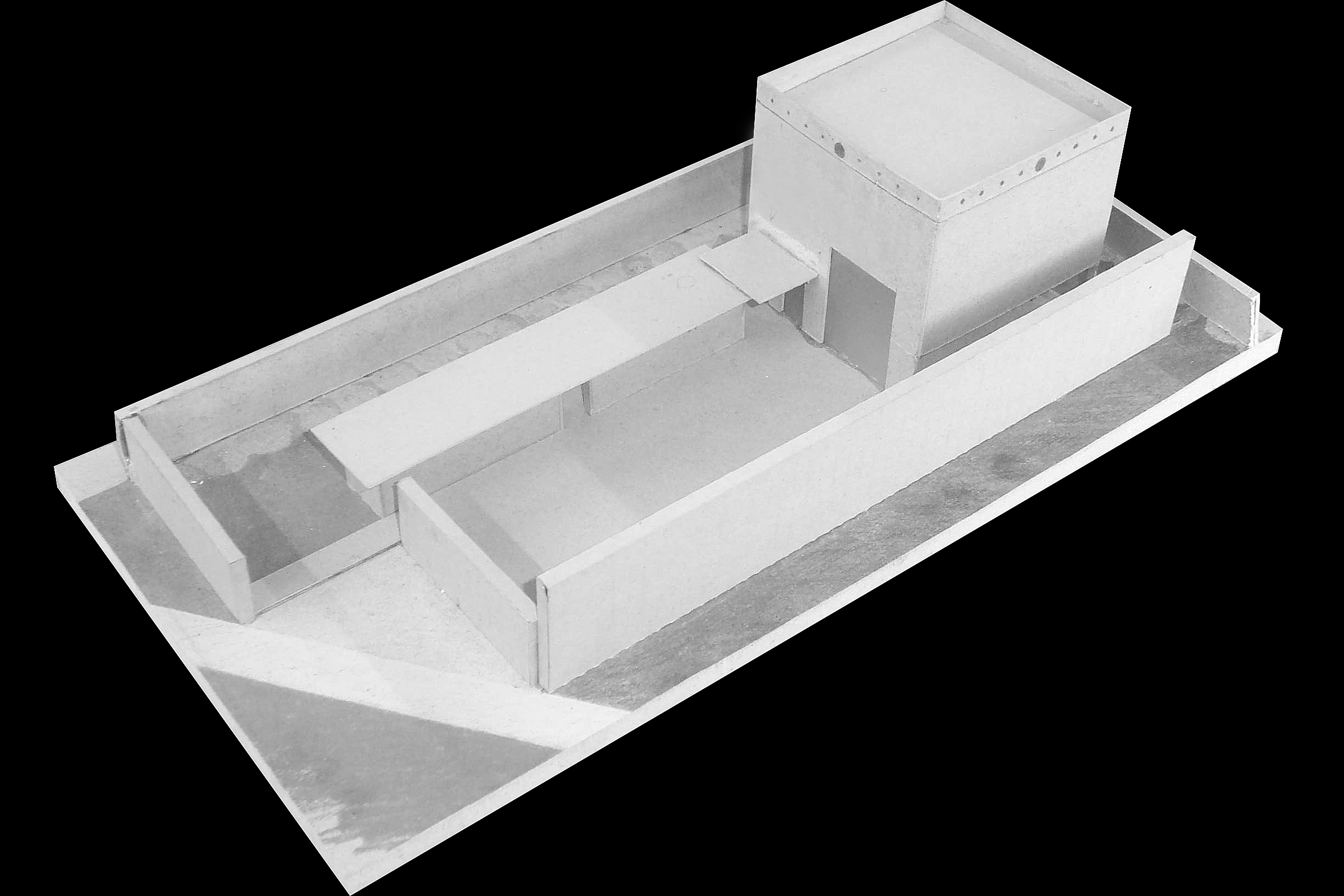

A MOSQUE IN GAZİOSMANPAŞA

Gaziosmanpaşa/İstanbul ︎ 1994 ︎ Construction Area: 330 m2 ︎ Site: 1.500 m2 ︎ Religious ︎ Nevzat Sayın, Tülay Atabey

It is very difficult to deal with a situation that has been predetermined by a higher authority. Moreover, if you do not personally have a ‘deep’ affinity with the subject, the ‘project’ becomes even more challenging. The mosque was such a subject for me. The spiritual connections of my childhood had gradually diminished and disappeared as I grew older. Nevertheless, I always had questions about mosque spaces that I found impressive. These questions arose especially when I was trying to understand how Turgut Cansever's statements on Islam were interpreted in the space.

The claim that ‘the mihrab wall was “privatised"' was not entirely convincing but provocative. The mihrab wall is the most important wall, and its significance is clearly conveyed through its architectural features and ornaments. Could "the most important" be obliterated and then reconstituted through its absence? This was the first question, and everything was determined accordingly. The mihrab wall was pushed back from its usual place and extended to form the mihrab wall of both the mosque and the outdoor prayer area, the namazgah. Two worship spaces, one enclosed and one open, were placed in front of and oriented towards this wall.

In addition to the indoor space, which could accommodate a hundred people, the outer prayer hall, namazgah, twice as large, provided the necessary space for Friday prayers in good weather. It also created a ceremonial effect along the path from the garden entrance by the road to the mosque entrance. Despite the "absence" of essential elements such as the minaret, dome, mihrab, pulpit, and minbar, there was still a mosque—in the conventional sense.